Engaging Stoicism II (2012)

Shortly after I wrote my post on Stoicism, I perused through my Evernote and noted a journal entry from 2012. It focuses on “living in the present” which, according to P. Hadot, is a central theme in both Stoicism and Epicureanism. What follows is the ensuing meditation for that day (with a brief editorial brush up). I still stand by those words.

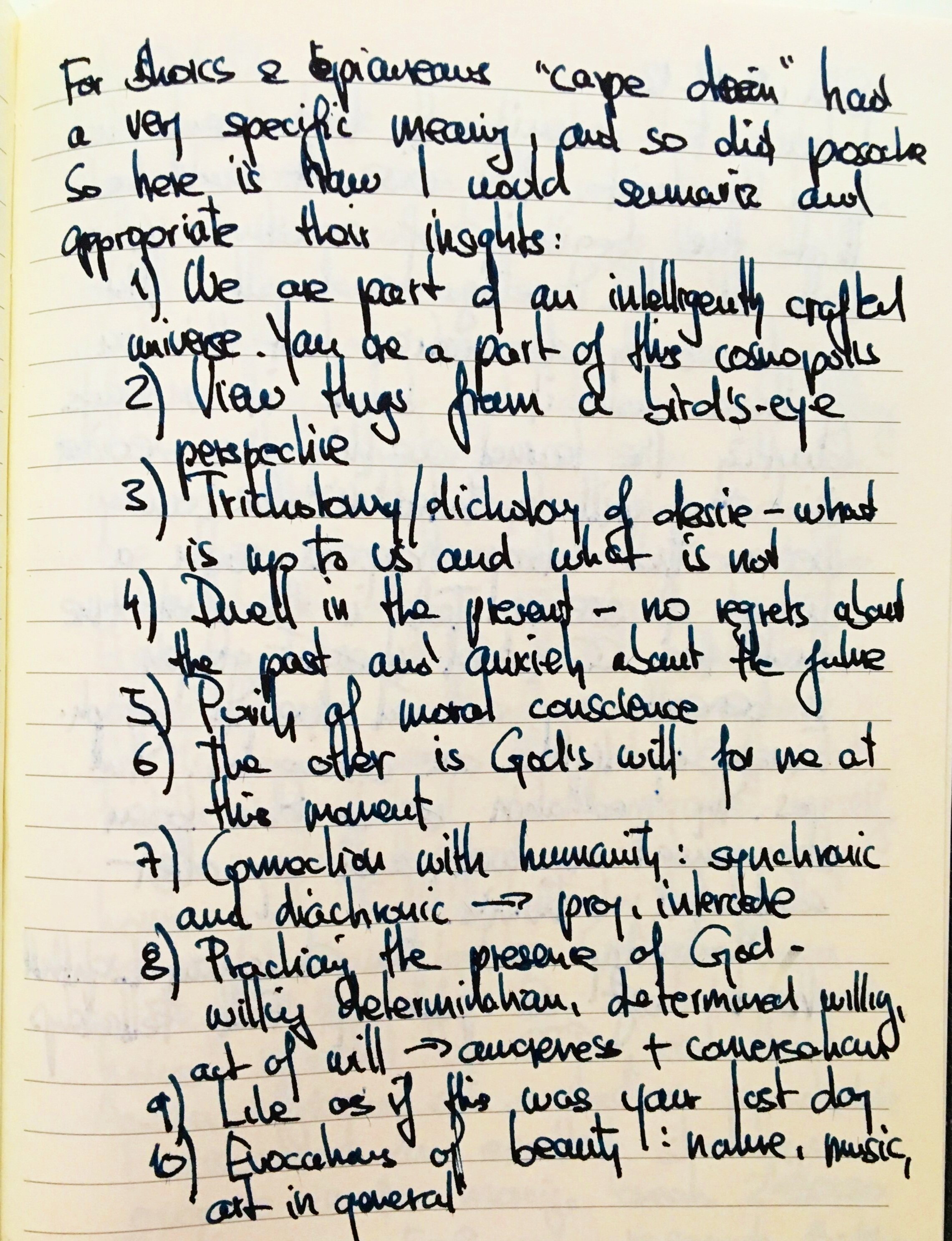

For the Stoics and Epicureans “carpe diem” had a very specific meaning, and so did prosoche (mindful attention). Here is how I would summarize and appropriate their insights (with minor editorial brush-up. I still stand by most of these observations.

We are a part of an intelligently crafted universe. You are a part of this cosmopolis.

View things from a bird’s-eye perspective.

Keep in mind the trichotomy/dichotomy of desire. In other words, what is up to us and what is not.

Dwell in the present. Have no regrets about the past or anxiety about the future.

Privilege the purity of moral conscience.

The Other is God's will for me in this moment.

Nurture a connection with humanity, both synchronically (in the present) and diachronically (historically). Do so by prayer, intercession, and remembrance.

Practicing the presence of God is about willing determination and determined willing, in other words, an act of will. Do so by nurturing an awareness of and conversation with the divine.

Live today as if it was your last day.

Discern the presence of God through evocations of beauty: nature, music, and art in general.