Existential Inventions

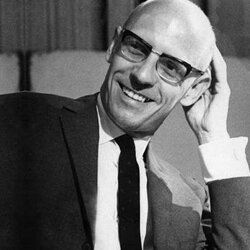

As an example of contrapuntal improvisation, inventio is the quintessential form of a musical exercise. In J. S. Bach’s work, inventions (or Aufrichtige Anleitugen) usually entail a short exposition, a longer development, and, sometimes, a short recapitulation (Invention # 5, for example). In contrast to the fugue, inventions do not generally contain an answer to the subject in the dominant key. They are less developed, less complete, not so grand. Frequently, the recapitulation is left open, hanging as it were, unfledged and without finality. Inventions are meant for developing students, for personal development of competence, and as a rule do not aspire to the limelight of concert halls, although many outstanding recordings of Bach's inventions exist (Glenn Gould!). When practiced regularly, they form the body to respond adequately to the stimuli of notes and measures, keys and metronomes. They require an embrace of askesis, a disciplined reiteration of practices whose stated aim is to turn us into proper practitioners, masters of the fundamentals of music performance. In a sense, they are both initiation rites and “technologies of the self” (Foucault), preludes to greater musical complexities with their balance of innovation and structure, predictability and surprise.

I want to utilize this simile of inventio as a symbolic shortcut for a particular existential style, a way of thinking about God, culture, and self through a cluster of interrelated metaphors: elaboration, incompleteness, discipline, practice, thematic unity, and performance...