"Straying Afield of Oneself"—Foucault and the Craft of Living

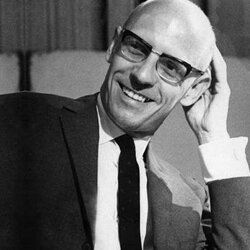

Let me begin with a few words from Michel Foucault’s The Uses of Pleasure:

As for what motivated me, it is quite simple…. It was curiosity—the only kind of curiosity, in any case, that is worth acting upon with a degree of obstinacy: not the curiosity that seeks to assimilate what it is proper for one to know, but that which enables one to get free of oneself. After all, what would be the value of the passion for knowledge if it resulted only in a certain amount of knowledgeableness and not, in one way or another and to the extent possible, in the knower’s straying afield of himself?… What is philosophy today—philosophical activity, I mean—if it is not the critical work that thought brings to bear on itself?… The essay—which should be understood as the assay or test by which, in the game of truth, one undergoes changes… is the living substance of philosophy, at least if we assume that philosophy is still what it was in times past, i.e., an “ascesis,” askesis, an exercise of oneself in the activity of thought.

There are many moving balls here, but what strikes me as deeply pertinent is his definition of philosophy as a type of askesis, “an exercise of oneself in the activity of thought”; a motto of the Craft of Living blog. More than simply striving to be informative, the posts are “athletic” feats of sorts, a type of spiritual calisthenics in the form of probing, experimenting, crafting, and holding myself accountable. They are implicit attempts to work on myself as myself, or, the appropriate Foucault’s gratifying turn of phrase, to foster the “knower’s straying afield of himself.”

I won’t go into what all that Foucault is after here, except to note his correct assumption that true philosophy amounts to a craft, an art of letting go of the self; the illusionary, obstinate, narcissistic, false, incongruous, lazy, bored self. A genuine Christian philosophy will, of course, understand such self-renunciation—the “I no longer live” aspect—entirely in christological terms.